BIENNALE ANYONE?

Why are there biennale exhibitions? It seems to be contagious (like a virus). First someone in Venice decides to hold a biennale exhibition in the 1980s and then, before you know it, biennales are everywhere: Lisbon, Buenos Aires, Chicago, Orleans, etc. The list goes on... What is the point? So much work goes into it! Huge teams are formed to laboriously conceive the contents and their ostensible purpose, to convince architects to participate and cities to fund it, to find sponsors, to organize and arrange the endless logistics...

What typically ends up being exhibited in a biennale is either specially-designed ephemeral work or secondhand accounts of something that went on elsewhere sometime before, either in the recent or more distant past—if distant, because it is supposedly exemplary, or if recent, because of its supposed novelty or originality. Most likely, the biennale, as its name suggests, happens not so much because, in the last two years so much was new or exemplary and now we need to share it, but rather simply because two years have already gone by and it is time to do it again.

FEEDING THE CITY!

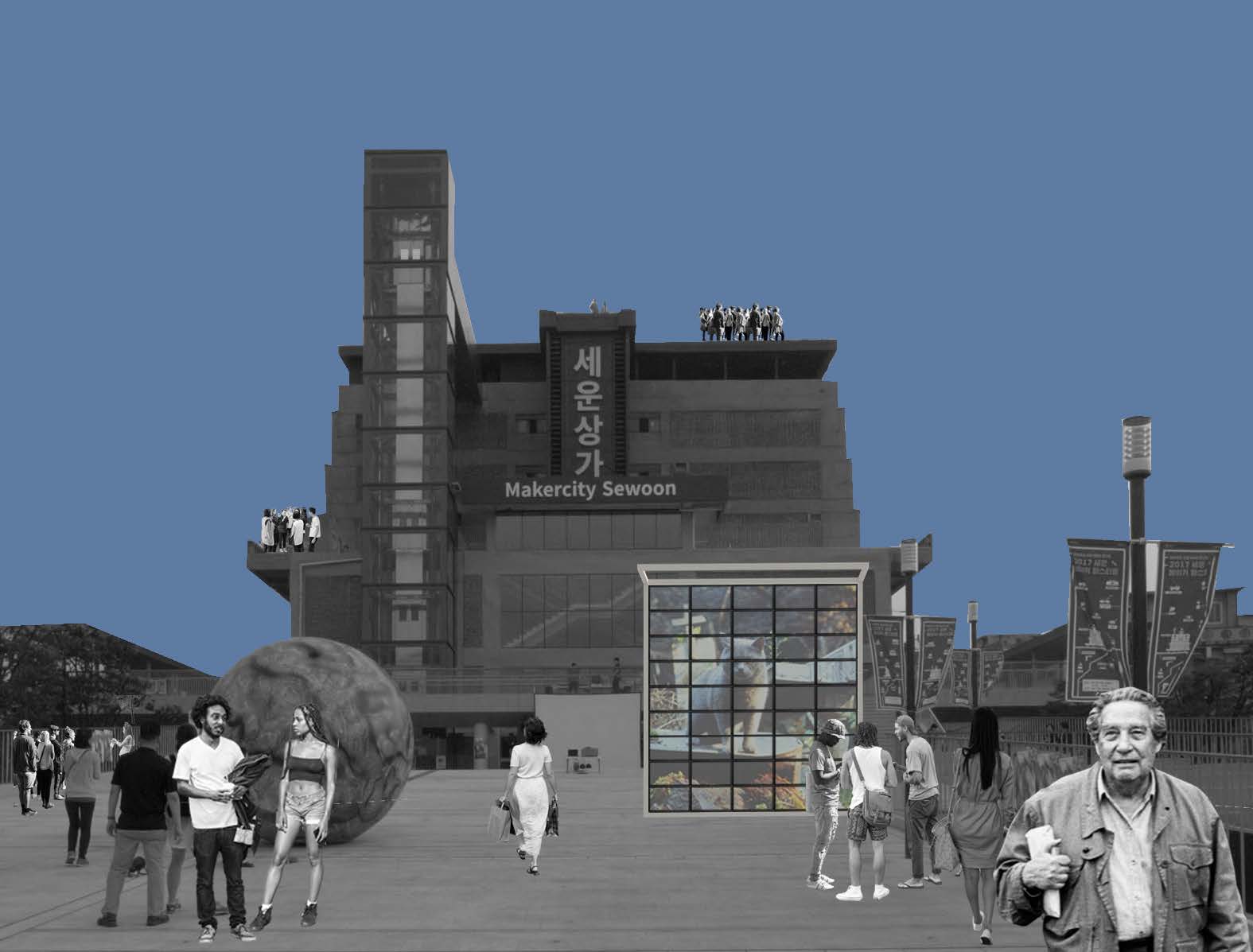

Whether a particular biennale might be “good” or “bad”—one either showcasing the new and innovative or a trite and fatigued production—a biennale is in itself a very good thing. Any community benefits from the recurrence of collective rituals that mark the passage oftime: any excuse is a good excuse for people meeting to do something together. As a matter of fact, ideally, the perfect society would be one existing in an almost permanent state of carnavalesque collective excitement periodically induced by biennale-like type of events. People are such that they need a continuous feed of incentives to periodically propel themselves forward into the unknown of new forms of being and thinking about themselves. It can become scary stuff, venturing into the unknown, but if done together, reassurance can be found in fellowship,and initial apprehension can become excitement and camaraderie. The encounter with what others do can incite in a person some pretty peculiar ideas: the possibility of becoming

someone else for example, of fulfilling some potential we didn’t even know we had. Let’s choose to think of a biennale as a thematic form of such collective reaffirmation, of what we all live for, after all. Let the biennale feed the imagination of the city with the manifold of possibilities of its future becoming!

THE PLAGUE

Now, of course, still under the grip of our self-imposed confinement, an urban carnival is urgently needed more than ever. At a moment when the future existence of the city is being

questioned by many, the return of the architecture biennale can be seen as the eruption of a ray of optimistic light into the dark room of collective depression, as the opportunity for a forceful reaffirmation of the enduring need for a city.

The biennale, in a way, can address the proliferating dull mob of the champions of the suburban exit and urban skeptics of any feather. To them we say:

1. Good riddance, you cowards!

2. Just know that the pandemic might have been unleashed not because we live too close together, but t because we live too far apart. Our culture has not been urban enough, only in a city-induced awareness of an unavoidably-collective destiny, will we find the protection against further nefarious consequences of a culture obsessed with a narcissistic individualism masquerading as hyperbolic “freedom.”

REDEMPTION

It is not by chance that the pandemic has hit the world at a tim of resurgence of authoritarian sentiment throughout the world, a sentiment that runs the deepest precisely in the countrie where the plague first appeared and where it hit the hardest. Only a renewed awareness of the need for personal civility—the sort of benevolent urbane guts required to live in the civitas—would set us up with the “immunological” guarantee for surviva and subsequent cultural, economical and social rebound: a redemption from the plague.